Massgames Pyongyang

Photo series about the Massgames in Pyongyang, North Korea

The greatest show on earth

Series of 10 photos published at Gallery Lumas

Now in an exclusive edition at Koryo Studio

More motifs via my website Massgames Pictures

Exhibited at the 25th International Poster Biennale in Warsaw 2016

The only German contribution to the North Korea special of Time Magazine 2018

Mode-Serie mit meinen Fotos

More information can be found on the Facebook page of the series

Elementor hat by default das erste Akkordeon Element immer geöffnet.

Dieses CSS lässt das erste Element verschwinden. Das hier ist also nur das Platzhalter Element, damit das Akkordeon geschlossen erscheint.

.elementor-accordion .elementor-accordion-item:first-of-type {

display: none;}Interview with Whitewall, the Lumas laboratory

Publication on the International Poster Biennale Warsaw in Eye-Magazine

Interview in the Welt (zum Bildband A Night in Pyongyang)

Report in the Huffington Post

Article in the & Livestyle-Blog Hypebeast

Article in the Design-Blog Designboom

Article in the art magazine Scene 360

Article in the Design-Blog Trendhunter

Article in the Daily Mail

Making of

The schoolchildren, conscious that a single slip in their action may spoil their mass gymnastic performance, make every effort to subordinate all their thoughts and actions to the collective.

Kim Jong-il, April 1987

Elementor hat by default das erste Akkordeon Element immer geöffnet.

Dieses CSS lässt das erste Element verschwinden. Das hier ist also nur das Platzhalter Element, damit das Akkordeon geschlossen erscheint.

.elementor-accordion .elementor-accordion-item:first-of-type {

display: none;}In June 1811, the first “gymnastics ground” was opened on Berlin’s Hasenheide by assistant teacher Friedrich Ludwig Jahn, later known as the “father of gymnastics”. Everyone was supposed to be able to gather here and exercise in public. However, the authorities eyed the rapidly growing gymnastics movement with suspicion, as Jahn was known as a radical nationalist who wanted to abolish the small state and dreamed of freedom, equality and a “Greater Germany” with a new capital “Teutonia” to be built in Thuringia. It is therefore not surprising that the gymnasts were banned again as early as 1820 and Jahn was arrested several times in the following years. It was not until 1842 that Wilhelm IV of Prussia lifted the “gymnastics ban” after Jahn had renounced his most radical political ideas. After this de-ideologisation, however, the movement became enormously popular. The Leipzig Gymnastics Festival of 1863 with over 20,000 participants is regarded as the first highlight.

When the idea of public mass gymnastics was rediscovered by various socialist states after the Second World War, a new political charge followed – apparently inevitably – but from a different direction. The synchronicity of the movements already introduced by Jahn was now taken to the extreme, as belief in the system and staging suddenly fitted together perfectly. North Korea’s ruler Kim Jong Il formulated this idea in an essay on “mass gymnastics” as follows: “Realising that the slightest mistake in their actions can disrupt the entire performance, the schoolchildren make every effort to subordinate all their thoughts and actions to the collective.” The individual therefore only functions as part of the collective, and the collective is only perfect if every individual is. The mass games serve as a path to becoming a “fully developed communist human being” (Kim Jong Il, ibid.). Equipped with this ideological framework, the North Korean mass games put everything that has ever been performed in the Eastern Bloc far in the shade and pack what has just been described into a show that is as gigantic as it is spectacular.

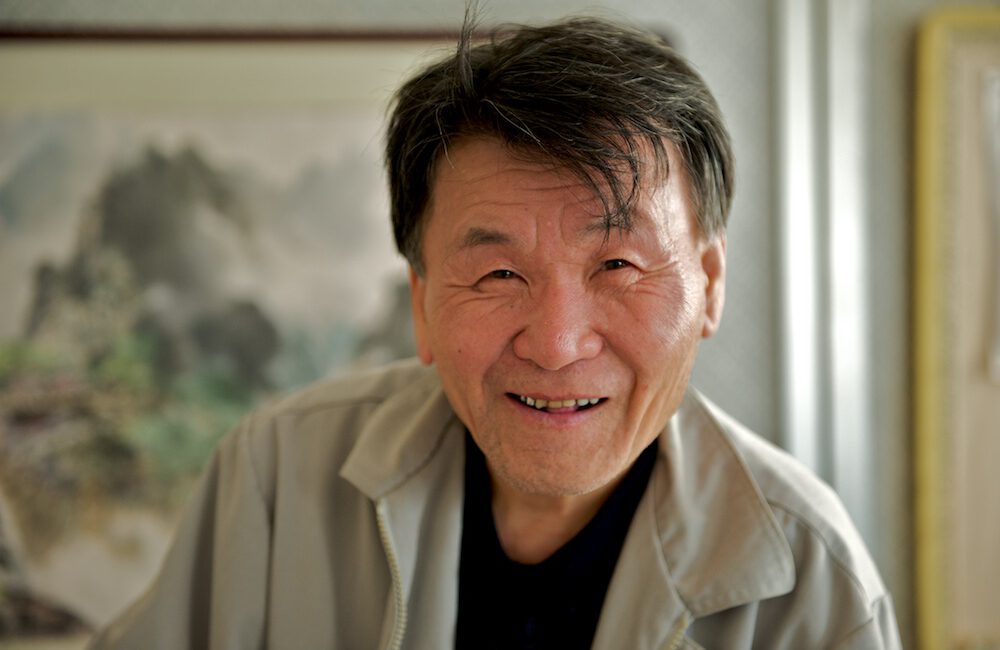

Through my picture book about the Massgames, I got in touch with the Lumas Gallery, which was very interested in my photos. However, as I only had a small amateur camera with me on my first trip, the resolution of the photos was not sufficient for the large formats that Lumas wanted. So I decided to take a second series. With decent equipment and an official photo licence. I was less interested in the spectacular long shots that Thomas Gursky, for example, had photographed. I wanted to find the “man in the masses”, to tear him out of the collective – and to do this I had to get as close as possible to the participants, either by getting close to the pitch or using extremely long focal lengths, preferably both.

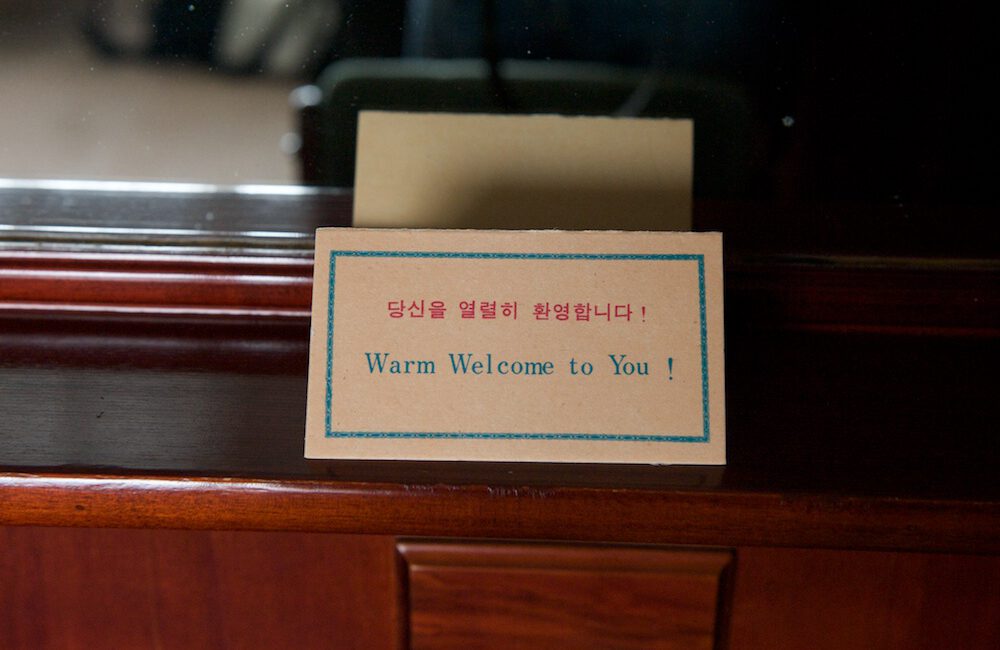

However, the photo permit presented me with almost insurmountable problems. For almost a year, I had to listen to people telling me that there was no way I could do that. In Pyongyang, however, my efforts were well recognised. A Korean employee of the German embassy researched how I had first come to the country and contacted Koryo Tours to tell them that a strange guy from Germany was currently scaring up everyone and anyone in Pyongyang with a request for a photo permit. Nick Bonner from Koryo Tours then offered me his help and things slowly started to move. At the end of the summer I finally got a message from Nick: a door might open for me in Pyongyang. The best thing would be to get on a plane and just go for it. I plucked up all my courage, plundered my bank account and travelled to the “hermit kingdom” in September. I still didn’t have an official photo permit, but I managed to get my equipment through customs and was standing in the stadium that same evening. My guide Mr Li proudly presented me with my box seat: there was a long row of heavy armchairs where North Korean celebrities, including Kim Jong-un himself, were attending the opening of the Mass Games. This was the best view – but the seats were unsuitable for my purposes as they were far too far away. I pointed to the rows below the box directly adjacent to the pitch: that’s where I wanted to go. Mr Li initially waved me off, but with a lot of patience and further difficult negotiations, two days later I was actually standing right at the front of the pitch – closer than any other photographer before me.

A week later I was back in Beijing. Exhausted, but with a treasure trove of photos in my luggage. In Pyongyang I had only had time to fly over the photos, now I could finally view them in peace. The close-ups I had fought so hard for were perfect. But to my horror, the long shots were all blurred. Apparently my wide-angle lens had been damaged during transport. The long shots weren’t the core of the work – but without them I wouldn’t be able to present the series at Lumas. So I flew back to Germany, replaced my lens and a few days later I was back in Pyongyang, much to the amazement of my guides. I was now a “third timer”, one of the few Western tourists who had been to North Korea three times. But the difficulties continued. Two of the three shows I had booked were cancelled. The only shows that still took place were outside the validity of my visa. Again, Mr Li made the impossible possible. I was in North Korea for a day without a visa, then he arranged an appointment in a café where Western tourists were not allowed. To my great delight, I met Ms Pak Hyon-yi – who had been my tour guide on my first trip. She was now the head of the state travel agency KITC – and she was able to help. My visa was extended that same evening and the next day I was back in the stadium at the greatest show on earth, camera in hand, carefully shooting long shot after long shot, crisp and unique.